Checking your immigration status

This page was last updated on: 15 December 2021

Many children and young people who arrived in the UK at a very young age and have lived here ever since may be undocumented. This means they might not have any legal immigration status.

If you were born outside the UK, several signs may indicate you don't have a legal immigration status:

- Since arriving in the UK as a child or a young person, have you left the country for:

a) School trips?

b) Family vacations?

c) Holidays with friends? - If you are age 16 and over:

a) Have you had your National Insurance number (NI)?

b) Are you able to apply for a provisional driving license?

c) Do you have the correct documents to prove you can legally work in the UK? - Do you have a bank account?

- Do you have a doctor (GP)?

- Can you gain access to college without difficulty?

- Can you gain access to student finance to go to your chosen university?

- Have you ever seen your passport?

If you answer ‘no’ to most of the above questions, you need to ask your parent(s) or guardian(s) about your immigration status.

If you are undocumented, you can face many problems including:

- you may be stopped from studying and attending university

- your bank accounts may be closed or you may be unable to open one

- you will find it hard to rent property (anyone renting a property to you has a legal duty to check your immigration status - this is called a ‘right to rent’ check)

- you may have to pay for medical treatment

- you will be unable to work. If you are working, this is considered a criminal offence

- restrictions on travel:

- you may not be able to travel outside the UK without documentation – for example, a valid passport

- if you do leave the UK and travel abroad, you may be unable to return if you don’t have a legal immigration status

- the government could try to send you back to your country of nationality

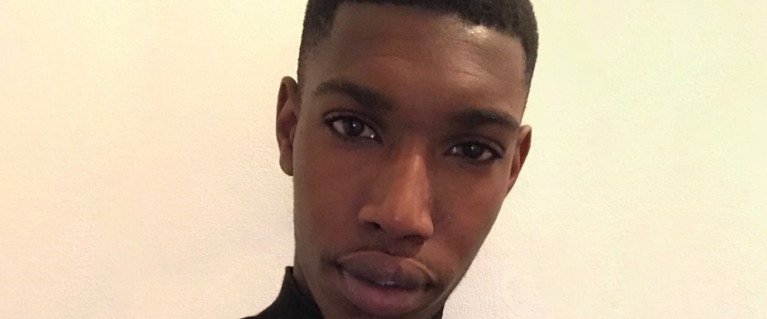

I was born and partially raised in South America, Georgetown, Guyana. I am the youngest of five siblings; I have two brothers and two sisters. As a young child I had little to no memory of my parents as my father lived in America and my mother moved to the UK when I was only 3 years old. Seven years later, a few months after my 10th birthday, I sat on a plane with my two brothers heading towards the UK – anxious to meet my mother for what felt like the first time ever.

After arriving in the UK, I attended school like any other child of my age. So, since the age of ten I have lived in London – this is my home. The idea that I was living illegally in this country never crossed my mind. However, when reflecting, there were always clues that something was not right. My brother who played semi-professional basketball was not able to play in Europe and had to give up his position in his team because he could not provide a valid passport or documents. I was not allowed to take school trips outside of the country and for many years we were constantly moving houses until we were at one point homeless. We were lucky to be aided by friends and family.

It was only between the ages of 16 and 17 when I began to understand my situation. On applying to university, I realised that I did not have the right documentation to access student finance: no British passport, and no limited leave to remain document to prove my legal residency. I spoke to my mother about this and she told me the truth about my situation – I was undocumented.

I wasted no time in seeking help. I contacted various organisations to ask for assistance. I spoke to my previous teachers about the issue and asked for advice. I found out about the high cost of the Home Office application to regularise my status and realised I could not possibly afford this. One organisation offered pro-bono help with my application because all access to legal aid had been removed a few years prior, but then their funding ran out. I finally reached out to all my friends and family and asked them to help us pay for our application. After several months we saved enough money to pay for a solicitor to help us with our Home Office application. We are still waiting for their decision.

Many children and young people who arrived in the UK at a very young age and have lived here ever since may be undocumented. This means they might not have any legal immigration status.

If you were born outside the UK, you should check your status.

If you were born in the UK, this does not mean that you are automatically a British citizen. A birth certificate showing that you were born in the UK may not be enough. This can be for a number of reasons.

You may not automatically be a British citizen if:

- At the time of your birth, your parents (either or both) did not have British citizenship

- At the time of your birth, your parents (either or both) did not have indefinite leave to remain or permanent residence in the UK

- At the time of your birth (after 01 July 2021) your parents did not receive EU Settlement Scheme Settled Status (this applies to children of EEA or Swiss citizens).

It is important to ask your parent(s) or guardian(s) about your immigration status. If you are not certain that your are a British citizen, you should check your status.

People normally get nationality at birth. In the UK, most people get their nationality from their parents. But sometimes people find that they are not legally a national of any country. This might be because the country their parents are from does not let them inherit their parents' nationality for some reason. For example:

- some countries do not accept children as nationals if they were born outside of that country and do not register with their embassy within a set amount of time

- some countries do not let women pass on their nationality to their children

- sometimes countries change their borders or new countries are created, and people are left unable to prove what country they belong to

People who are legally not a citizen of any country can apply to stay in the UK as a 'stateless' person. If you think you might be stateless you should check your status, and then read Coram Children's Legal Centre's fact sheet for more information about what to do next.

EEA Nationals:

- those who are nationals (holding a passport) from the following countries: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden. People from Switzerland are also counted as ‘EEA Nationals’ for the purpose of this guidance.

Status:

- the right to live in the UK

No legal immigration status:

- this means you have no legal right to live in the UK

British citizen:

- someone who has the right to hold a British passport

Limited leave to remain:

- this is a lawful immigration status. It means that you have the right to live and work in the UK, usually for 30 months. You must renew this status before it expires.

Biometric residence permit:

- a card that will be sent to you by the Home Office after you have been granted limited leave to remain. This card is ID. It will have your picture, name, date of birth and fingerprint. It will also have the start and expiration date of your status.

NHS surcharge:

- a fee that you must pay to access NHS services. This fee must be paid when you are applying or reapplying for limited leave to remain.

Need a document on this page in an accessible format?

If you use assistive technology (such as a screen reader) and need a version of a PDF or other document on this page in a more accessible format, please get in touch via our online form and tell us which format you need.

It will also help us if you tell us which assistive technology you use. We’ll consider your request and get back to you in 5 working days.